Why Price Controls Always Fail: A Lesson from the National Industrial Recovery Act

As Politicians Renew Calls for Price Controls to Combat Inflation, History Offers a Cautionary Tale on the Economic Costs and Inefficiencies of Government Intervention.

Introduction

In recent weeks, there has been a resurgence of politicians and policymakers advocating for price controls as a solution to rising inflation. This is despite a wealth of economic history and theory that clearly demonstrates the dangers and inefficacy of such measures. One of the most well-documented examples of the failure of price controls is the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) of 1933, enacted during the Great Depression. The NIRA was an ambitious attempt by the U.S. government to control prices, wages, and production to stabilize the economy. However, it ultimately failed, leading to increased economic inefficiencies, reduced production, and higher unemployment.

This paper explores why the NIRA's approach to price setting was flawed, drawing on the economic theories of Friedrich Hayek and Ludwig von Mises to explain the importance of free market prices. We will also examine the specific economic costs of the NIRA, demonstrating how its policies exacerbated the very problems it was designed to solve. By revisiting this historical case, we aim to underscore the fundamental principle that price controls do not work and often lead to unintended negative consequences.

Understanding Prices: The Theories of Hayek and Mises

To understand why the NIRA’s price-setting mechanisms failed, it’s essential first to grasp the role of prices in a market economy as articulated by Friedrich Hayek and Ludwig von Mises. Their insights provide a foundational understanding of why free market prices are crucial for economic efficiency and stability.

What Are Prices?

At their core, prices are more than just the amount of money you pay for something; they are signals that convey important information about goods and services. Prices reflect the collective actions and decisions of millions of individuals in the market, each with their own needs, preferences, and resources. Friedrich Hayek famously described prices as a "mechanism for communicating information" ("Prices and Production and Other Works"). But what does this mean in everyday terms?

Imagine you’re at the grocery store, and you notice that the price of apples has gone up. This price increase is not arbitrary. It likely reflects a change in the conditions of apple production—perhaps a poor harvest has reduced supply, or maybe there’s increased demand because apples are in season and more people are buying them. The higher price signals to consumers that apples are scarcer and encourages them to buy less or consider substitutes like oranges. At the same time, it signals to farmers that apples have become more valuable, encouraging them to produce more if possible.

This process happens naturally and continuously in a free market. Prices adjust to reflect changes in supply and demand, ensuring that resources are allocated efficiently. If prices are allowed to do their job, they help prevent shortages and surpluses, guiding both producers and consumers to make decisions that align with the overall needs of society.

How Are Prices Determined?

Prices are determined through the interaction of supply and demand. Let’s break this down with a simple example:

Suppose you own a small bakery that sells bread. You notice that the price of flour—your main ingredient—has increased. This could be due to a variety of reasons: a bad wheat harvest, increased transportation costs, or even higher demand from other bakeries. Because flour is more expensive, your costs of making bread go up. To stay profitable, you decide to raise the price of your bread.

Your customers, seeing the higher price, might buy a little less bread or switch to a cheaper alternative. This decrease in demand might eventually lead you to adjust your prices again or find ways to reduce costs. Conversely, if the price of flour drops, you might lower your bread prices to attract more customers.

This continuous back-and-forth between what consumers are willing to pay and what producers need to cover their costs is how prices are determined in a free market. When left undisturbed, this system naturally balances itself, ensuring that goods and services are produced and consumed at levels that reflect their true value to society.

Why Are Prices Important?

Hayek and Mises argue that prices are crucial because they incorporate and reflect the knowledge of countless individuals in society. No single person or government can know everything about the economy—what goods are in demand, how much it costs to produce them, or what resources are available. However, prices allow everyone to act as if they had more knowledge than they actually do.

For example, if the price of gasoline rises, you might decide to drive less or switch to a more fuel-efficient car, even if you don’t know the exact reasons behind the price increase. The higher price communicates that gasoline is now scarcer or more expensive to produce, and your response helps reduce demand, aligning consumption with the available supply.

This decentralized decision-making process is what makes the free market so effective. Prices guide resources to where they are most needed, helping to ensure that goods and services are produced efficiently and in quantities that meet demand. When prices are set by the government rather than the market, this process is disrupted, leading to misallocations of resources, inefficiencies, and often economic hardship.

The National Industrial Recovery Act: Objectives and Structure

What Led to the Passage of the NIRA?

The NIRA was enacted during the Great Depression, a time of unprecedented economic turmoil. By 1933, the U.S. economy had collapsed, with industrial production plummeting, unemployment soaring, and widespread poverty. The Roosevelt administration believed that direct government intervention was necessary to stabilize the economy, protect jobs, and revive industries.

The NIRA was conceived as a way to control competition, stabilize prices, and boost wages by creating industry codes that businesses were required to follow. These codes set prices, wages, and production levels in an attempt to prevent what was seen as "cut-throat competition" that could drive companies out of business and further deepen the economic crisis.

Objectives of the NIRA

The primary objectives of the NIRA were:

Revive Industrial Production: By reducing competition and stabilizing prices, the Act aimed to prevent the collapse of businesses and revitalize industries.

Increase Employment: The NIRA sought to create more jobs by setting minimum wages and limiting working hours, which would force companies to hire more workers.

Stimulate Demand: By increasing wages, the Act aimed to boost consumer purchasing power, leading to higher demand for goods and services.

How the NIRA Was Structured and Functioned

Structure of the NIRA

The NIRA established the National Recovery Administration (NRA) to oversee the creation and enforcement of industry codes. These codes were essentially agreements among businesses within the same industry to follow specific rules on prices, wages, and production. Over 700 industry codes were developed, covering a wide range of economic activities.

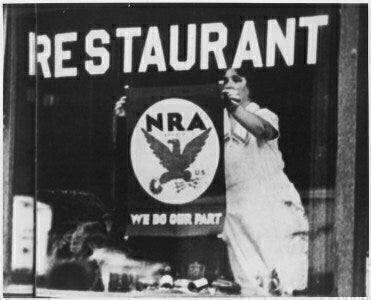

The NRA encouraged businesses to comply with these codes by allowing them to display the Blue Eagle emblem, a symbol of patriotic cooperation with the government’s recovery efforts. The idea was that consumers would prefer to buy from businesses that adhered to these standards, thus pressuring companies to comply.

How It Functioned

In practice, the NIRA created government-backed cartels in various industries. These cartels were legally enforced, with businesses that failed to comply facing fines, imprisonment, or the loss of the Blue Eagle emblem, which could lead to consumer boycotts. The NIRA’s approach was to manage the economy from the top down, with the government dictating prices, wages, and production quotas ("An Anatomy of a Cartel: The National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 and the Compliance Crisis of 1934").

The Economic Costs of the NIRA

While the NIRA was designed to stabilize the economy, its policies led to significant economic costs that exacerbated the very problems it was intended to solve.

Inefficiencies and Reduced Production

One of the most significant economic costs of the NIRA was the inefficiency it introduced into the market. By setting prices and wages above what the market would naturally determine, the NIRA distorted the price signals that guide efficient resource allocation. For example, in the steel industry, the NIRA codes required companies to set prices that were higher than what the market would have established. This made steel more expensive, reduced demand, and led to lower production levels overall. Instead of encouraging industrial recovery, these price controls stifled competition and innovation, leading to reduced output and higher costs for consumers ("An Anatomy of a Cartel").

Increased Unemployment

The NIRA's wage-setting provisions also had unintended consequences for employment. While the Act aimed to increase wages to boost consumer demand, it did so without considering the productivity of workers. As a result, businesses faced higher labor costs without a corresponding increase in worker productivity. This led many companies to reduce their workforce or avoid hiring altogether, increasing unemployment instead of reducing it. For example, wages in industries covered by the NIRA codes rose by about 23% within a year of the Act’s passage, but this wage increase often came at the cost of jobs, as businesses could not afford to maintain their existing workforce at these higher wages ("An Anatomy of a Cartel").

The Compliance Crisis

A significant economic cost of the NIRA was the compliance crisis that emerged shortly after its implementation. Initially, businesses complied with the NIRA codes out of fear of government penalties and the potential loss of the Blue Eagle emblem. However, as it became clear that the government lacked the resources to enforce the codes consistently, compliance began to break down. Businesses started to defect from the codes, undermining the entire system. This compliance crisis revealed the inherent flaw in trying to control prices and wages through government intervention: without voluntary adherence, such a system cannot sustain itself ("An Anatomy of a Cartel").

Why the NIRA Failed: Applying Mises and Hayek’s Price Theory

The Importance of Free Market Prices

Mises and Hayek argued that prices set by the free market are essential for the efficient functioning of an economy. Free market prices reflect the true value of goods and services based on supply and demand, allowing for the optimal allocation of resources. When prices are allowed to adjust naturally, they signal toproducers and consumers how to act in ways that maximize the overall welfare of society. This natural adjustment process ensures that resources are used where they are most needed and that goods and services are produced in the right quantities.

The Consequences of Government-Set Prices

The NIRA’s failure provides a clear example of the negative consequences of government-set prices. By fixing prices and wages, the NIRA disrupted the natural price signals that a free market relies on. This led to a misallocation of resources, with some sectors producing too much and others producing too little. For instance, in industries where the NIRA codes set prices above the market level, demand decreased, leading to lower production and higher costs. In other industries, where wages were set higher than the productivity levels warranted, businesses were forced to lay off workers or reduce hiring, increasing unemployment.

One illustrative example is the textile industry, where the NIRA’s wage mandates led to significant layoffs. While the Act aimed to improve workers' wages, it did so without regard to the industry's ability to pay these wages. As a result, many textile mills reduced their workforce to remain financially viable, leading to increased unemployment in an industry that the NIRA was supposed to protect.

Moreover, the breakdown in compliance further illustrates the dangers of trying to control prices through government intervention. As businesses realized that the government could not consistently enforce the NIRA codes, they began to ignore the regulations, leading to widespread defection from the rules. This compliance crisis not only undermined the NIRA’s goals but also highlighted the inherent difficulty in enforcing such wide-reaching economic controls.

Conclusion

The failure of the NIRA serves as a powerful lesson in the dangers of government price setting. As Friedrich Hayek and Ludwig von Mises have demonstrated through their economic theories, prices are critical signals that guide the efficient allocation of resources in a free market. When these signals are distorted by government intervention, as they were under the NIRA, the result is often economic inefficiency, reduced production, and increased unemployment—outcomes that are the opposite of what such interventions are intended to achieve.

In light of recent calls for price controls to combat inflation, it is crucial to remember the lessons of the NIRA. Price controls do not work and can lead to severe economic consequences. Instead, allowing prices to be determined by the free market is essential for ensuring economic stability and growth. The NIRA’s failure underscores the importance of respecting the natural price mechanisms of the market, which are vital for the efficient functioning of the economy.

References

Hayek, Friedrich A. The Use of Knowledge in Society. The American Economic Review, Vol. 35, No. 4, 1945, pp. 519-530.

Hayek, Friedrich A. Prices and Production and Other Works. Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2008.

Mises, Ludwig von. Human Action: A Treatise on Economics. Ludwig von Mises Institute, 1998.

Taylor, Jason E., and Peter G. Klein. "An Anatomy of a Cartel: The National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 and the Compliance Crisis of 1934." Research in Economic History, vol. 26, 2008.

Gordon, Robert Aaron. Business Recovery Through National Planning: America Tries Recovery Under the National Industrial Recovery Act (1933-1935). Unpublished manuscript, 2005.

Monroe, Thomas M. National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933: Legislative History. U.S. Government Printing Office, 1935.